Fallout 4 is big, and not just “sales” or “playable hours” big. It’s the latest installment in a franchise that’s been around for 18 years and has more than 200 years and five main games (Fallout: New Vegas absolutely counts as main) worth of fictional history. It’s also the latest example of big games based all around choices.

With all that history behind it, I started the game wondering if it could satisfy all the choices I’d made throughout that time, or if it would fall into the same trap so many other games focused around choice tend to do.

Fallout 4 still has plenty of great choices to make. For example, you can decide to make your character a cruel barbarian launching missiles at everyone they meet while wearing a mail carrier uniform. Those kind of character choices are still plenty and fruitful. It’s the other kind of choice, the story-based ones developers so often emphasize in previews and press events, where some cracks start to show.

The first problem was that there’s no connection to all the choices made in previous Fallouts. Obviously, carrying choices over from Fallout 1 & 2 would be more than a little difficult, but Fallout 3 and New Vegas were both on the last generation of consoles. Bioware was able to mount that hurdle for last year’s Dragon Age: Inquisition with their nifty Keep web browser tool that gave players granular control over specific choices made during earlier games. The Witcher 3 kept it simple by giving you dialogue choices that allowed you to establish your Witcher 2 choices by implying them.

I’m not expecting or asking for Fallout or all RPGs in a post-Keep world to have that kind of functionality. That’s a development burden; but, more importantly, it’s a narrative choice that is always up to the developer to make.

Fallout 4 seems at first like they’ve decided to keep things simple by not engaging at all with the choices of the older games. There’s no save transfer, no dialogue choices, no nothing, or so it seems. The problem is that the game dips its toe into the water of Fallout 3’s big choices in a way that’s more painful than it is tantalizing. Some references that would otherwise be cute easter eggs giving a nod to the previous game instead become a confirmation that things played out a certain way, regardless of how they might have when you experienced them years ago.

At first it seems like they’d made a completely unconnected story, but instead the break isn’t clean, or at least not clean enough.

There are all kinds of arguments to be made about authorial control, sure, but in a world changed not just by the infamous Mass Effect 3 extended ending and surrounding controversy (when Bioware altered and added to the final cutscene after fan outcry) but also Fallout 3’s own DLC Broken Steel (which similarly reversed the consequence of the main game’s final choice) it’s hard not to at least entertain thoughts that things could have been better.

On the other hand, it’s not hard to see why Bethesda wouldn’t want to carry choices over. The Mass Effect series was built from the ground up to have player choice impact the story throughout all three games and one of the most common criticisms of the conclusion was how weakly it delivered on that promise.

For instance, you had the choice of killing or saving the queen of a race of insect aliens in the first game. By the third, she was either there and corrupted by the bad guys or replaced by a robot version, or something. It was functionally indistinguishable; the choice didn’t matter even in a game built to make them matter. Blaming Bethesda for wanting to avoid that kind of mess, not to mention development costs, is hard to do.

What hurts then, is when thinking about the reality of building a game around choices starts to affect playing a game around choices. That happens in two ways. One, which similarly happened in Inquisition, was making story choices around the expectation of future content.

With Broken Steel seared in my mind, I found myself making choices based not on whether I wanted to see the story progress that way or if I thought it was what my character might do, but rather if those choices would preclude me from something in DLC or a sequel. My fault, maybe, but by the end of the game it had definitely negatively affected my experience with the story.

The other is when rather than seeing problems with the choices you can make, you start to see the choices they don’t let you make. In Inquisition and Mass Effect 3 you couldn’t make choices about troop movements or which planet to save, despite being told at every turn what an important supreme commander hero type you are. In Fallout 4 it was when, after being elected head of The Institute, you had no control over their projects.

The particular instance that comes to mind regards the Warwick family. You can encounter this family of seemingly normal people out in the world, but a terminal in the Institute reveals the father had been kidnapped, killed, and replaced with a synth. As Director of The Institute, that was a policy that had to go. But no, there is no choice to do that. It can’t even be brought up with any characters to explain that. Another glaring example is finding out the mayor of Diamond City is a synth, but not being able to tell a companion (whose introduction is all about her investigating if the mayor is a synth) anything about that!

The inability to making certain choices or worrying about choices not resulting in anything until three years and a sequel later has become a glaring flaw of big budget choice games. It’s a flaw that becomes even more evident in comparison to some smaller games that deliver so well on the idea of choice.

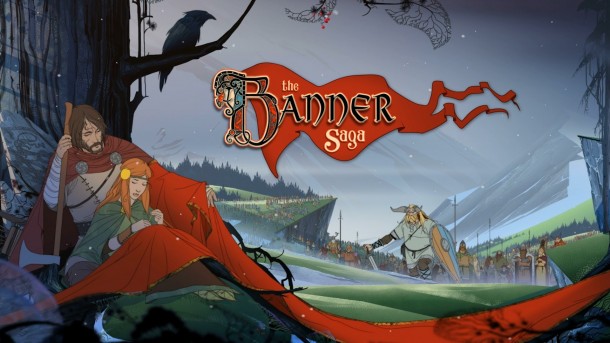

Take The Banner Saga. 2014’s tactical role-playing game had choices that affected gameplay, that changed the story immediately and in the long term, and looked sure to matter hugely in the sequel. Characters could die, permanently in-story, in combat just as easily as they could from dialogue-based decisions. One memorable choice let you decide to let a warrior and his companions join you. You got the immediate benefit of some extra soldiers, only to have him shank your friend and steal your stuff many hours after the fact.

Even when you didn’t really have a choice, you could at least try the other way. Halfway through the game, with the enemy literally at your door, you could decide to sabotage the sacred bridge to prevent them from reaching you, you can try and fight them back, or you can just leave and abandon your allies. If you try and fight them back you realize that your efforts are futile. You have to destroy the bridge or leave. But you could try fighting, and you can be sure destroying that sacred bridge and the alliance it held will come back to bite you in the sequel.

Developing for a game like The Banner Saga versus Fallout 4 is a hugely different process. It’s easier to account for more and more variables when your game doesn’t have to be voiced, doesn’t have to wrangle with a buggy graphics engine that powers a huge open world, and is only a few hours long. I get it.

But I’ll never forget the time in 2006 when Bioware said Mass Effect was going to make your choices matter. I haven’t forgotten all the press conferences and magazine interviews since where developer after developer says much the same. I sure haven’t forgotten when Bethesda made it clear their authorial intent was to sell you Broken Steel. Maybe it’s time for AAA developers to put up or shut up when it comes to choices.

No Comments