“Please come pick us up. We want to come home.”

The call from my grandmother was jarring. It was early on a Sunday morning in 2001 when the phone rang, and a very distraught Baba — Macedonian for “Grandma” — was in tears, calling us from a neighbor’s house. They had been attacked in their home the night before. “Freedom fighters” from the rebellious minority army had broken into their quiet village home and beaten them with the butts of their assault rifles. My grandfather’s face was swollen, with the neighbors applying ice to him in a hidden room in their basement.

Their house had been invaded at around 2AM, and they were the only ones home. Both in their late 80s, they couldn’t do much beyond submit to the whims of the two men with guns. The insurgents were looking for anything that they could steal — money, weapons, passports — and any reason to further injure the elderly couple. They lay in bed, crying, beaten, as the men ransacked their home, breaking picture frames and furniture and memories. After an hour or so of finding little they left. My grandfather was smart enough to have built hiding spots throughout his home for documents, and so at least their financial well being and identification papers were secure. Their neighbors, an Albanian family that had lived next door for decades, took them in and hid them for a few nights until they could come home.

It didn’t matter who was wrong or right in the war, at least not to my grandparents. They just wanted to survive it.

“Please come pick us up. We want to come home.”

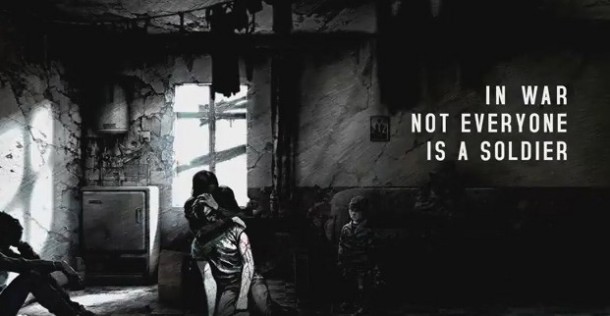

I was a little hesitant to take a look at This War of Mine, the upcoming game from 11-Bit Studios, last weekend at PAX East. The game, set in a war-torn city, looks at war and conflict from the victims’ standpoints. It’s not Call of Duty, it’s not Battlefield. It’s more Walking Dead than it is anything else. In a way that’s a fitting explanation: survival, at all costs, is the most important thing during war, whether that is against zombies or against men.

“War makes us the same,” Senior Writer Pawel Miechowski tells me as we play the game. “Food, water, the struggle for life are what guide us, not sides.” When the game was announced, some backlash came from the gamers who wanted an experience baked in entertainment and scoring, not mature subjects or to pull the strings of our emotions.

The team was inspired by “One Year in Hell“, a recent article about the Balkan wars of the 90s from one of the survivors. “He talked about how you survive, what you have to do, what steps you have to take.” Though surviving seems like an obvious choice, it’s not black and white, and This War of Mine reflects that. “There is no wrong or right or moral choice (in the game). The game is a tool to experience war on your own.” As we played through the demo session, I fully grasped what that meant.

The game is designed in 2D, much like a platformer, but through point-and-click action selections. The art direction is striking, matching the tone of the game. It mixes the desolate grays of the destroyed (unnamed) city with sketch-like brush strokes to the linework. Decisions in war have rough edges. The characters in the game are based on the development team. They’ve incorporated their likenesses — their faces and names, animations and personalities — into the situations. “We wanted this to feel as real as possible.” The team is even discussing the possibility for players to put their own selves into the game.

We begin in a small room of a building just as the war has begun. I’m there with my wife (or girlfriend?) Katia and friend Pavle. The first night there I put Pavle in charge of guarding the premises while Katia rested. I explored the building, finding a useful kitchen and an area to craft tools. As my energy drained, I opted to complete the night and rest. This War of Mine has a daily clock that determines when night and day start and end; leaving during the day means increased chances of running into the military or getting injured. It’s best to move around at night time. Each day we can select different actions for our group members. We can have them rest, eat, craft or guard. We can send a few out to scavenge, dividing up the weapons and tools as needed. The game’s length is also random. “In war, you never know when it will end,” Miechowski says. “It may be weeks, or it may be months. You just have to survive for as long as you can.”

This includes leaving the confines of the building we are in to explore the surroundings. I’d imagine in real life we’d know our surroundings well, but during war a lot of what we know changes. We’d no longer be afraid to enter someone else’s home looking for supplies. These supplies can include basic items like food or water or matches, or they may be pieces of wood or cloth or shards of metal that we craft into beds or weapons or water filters. One of the most important things we end up crafting is alcohol. As a tool, it can be used for fuel. It can also be medicine to clean wounds. It can be used to trade for other items. Or, we can drink it to momentarily give us reprieve from what is going on around us.

Trading becomes important, as the more we explore our surroundings, the more that necessary items can only be attained quickly by bartering for them with other survivors (or even the military). Our area starts out small, just the building we are in, but soon we can explore a few local businesses and depots and other homes. Five days in, Katia becomes incredibly sick and I need to find medicine. Instead of going out further and further, potentially risking her well-being, I decide that it’s worth trading with members of a local militia that have taken up in a nearby apartment building. They want weapons, however, and all I have are my fists.

As I made my way into an adjacent building hunting for firearms, I encounter another survivor scavenging. Do I approach them? Sneak past? Do I engage them in a fight to steal their wares? How important is Katia to me that I would abandon moral choice? Without a weapon to protect myself or fight, I choose to try and barter with them. As our conversation starts and things begin to move in my favor, the other survivor hears someone upstairs and runs away before I can gain any items. I also run, but head into the basement to poke around for tools while this mysterious third person ransacks a bedroom above me. Day is almost here, and with the upstairs occupied I choose to block the door and spend the night there in safety.

Pavel, who has been on guard duty, has become increasingly aggravated towards my favoritism of Katia. War can be as much about cooperation as survival. Though we begin with a small group, that can change over time. People will join, each bringing different skillsets with them. Or, they may leave or die, depending on how they’re treated or taken care of. We decide if people are good for the groups or detrimental to us, and what consequences they should face. In one example, both Pavle and Katia are hungry, and I’m increasingly growing weak. I have one piece of food. Do I share it? Give it to the sickest? Do I eat it to have just a bit more energy to head out and scavenge? And if I die or get trapped while scavenging, then my eating of the food can lead to dire consequences to the rest of the group.

“That’s why we didn’t have a morality tree. That’s why we want people to make their own decisions about how to survive the war.”

I know my grandparents went through hardship trying to survive being in the middle of a war. I know many of my relatives in Eastern Europe did, guarding their homes with shotguns and rifles for weeks on end. I probably and hopefully never will, but this game has the potential to at least give me a small bitter taste of what that experience was.

I left the demo on the loud PAX show floor, shaking Pawel’s hand and walking away with a forced smile. The smile quickly broke into an empty, hollow expression as I remembered the poignant words that my Grandfather told me when I saw him again:

“We didn’t care that they took our house. We didn’t care that they took our money, or our wedding rings, or our car. We didn’t care what side they were on. We just wanted to get out of there, to make it back to someplace safe. We just wanted to survive.”

They survived, barely.

When the game releases later this year on PCs and mobile devices, This War of Mine will be a very different experience from how we’ve experienced video game war in recent years. It’ll be just a digital interpretation of the plight that my grandparents went through, and a fraction at that, but perhaps one that can help educate me and others on what war really is. It’s not black and white.

![[PAX East 14] This War of Mine took an emotional toll on me](https://www.sidequesting.com/wp-content/uploads/This-War-Of-Mine-Logo.jpg)

3 Comments